Go to your broken heart. If you think you don't have one, get one.

On Jack Hirschman and the power of mentorship.

Jack Hirschman was, but his poetry still is.

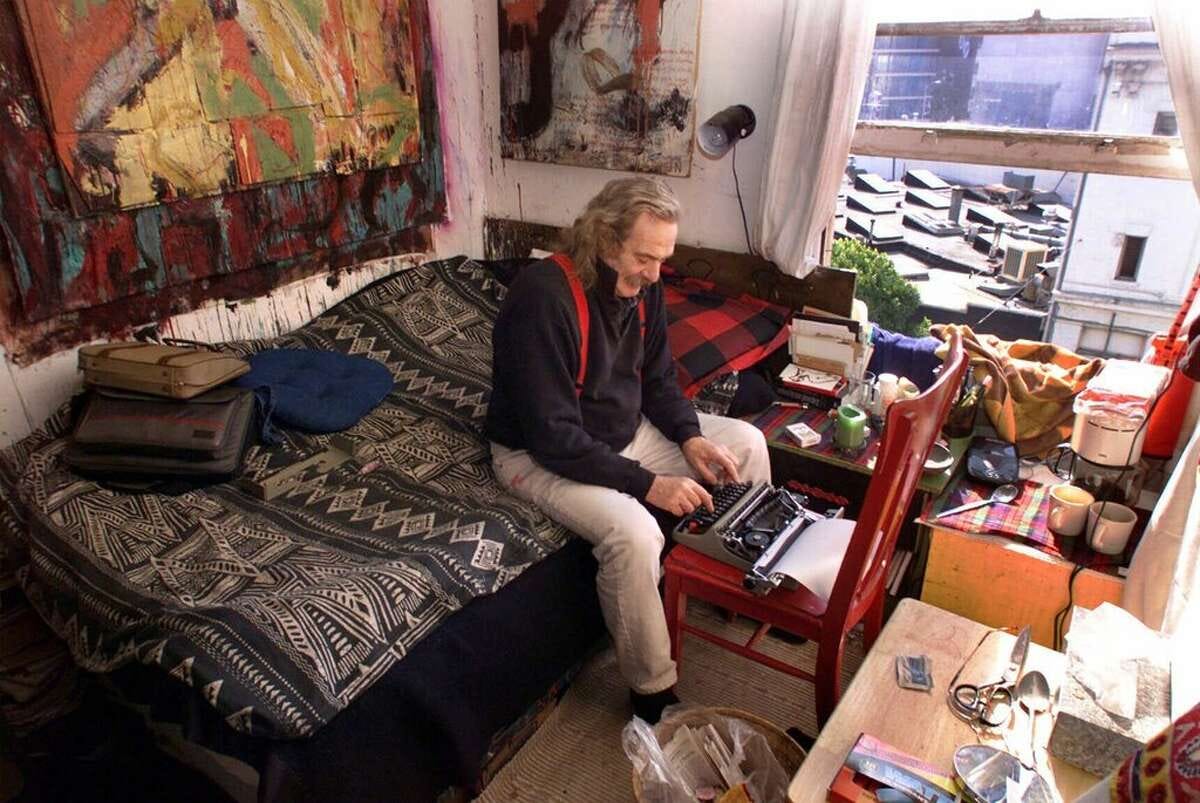

Jack was a brilliant and prolific poet who became my writing mentor when I was as young as 10 years old. He was a best friend of my father, and I had known him since I was in diapers. He lived a singular, remarkable life, from corresponding with Ernest Hemingway as a young man to becoming the Poet Laureate of San Francisco. Jack defied the hypocrisy of institutions and corporations, even when it put his early academic career on the line; during the Vietnam War, he was fired from his position as a university professor for giving students automatic A grades so they wouldn't be drafted. He went on to become instrumental in the Beat poetry movement of the 1960s, but unlike many of the writers whose identities were born from, and remained attached to, the Beat movement, he outgrew the typecast.

Jack was considered the People’s Poet, devoting his entire life to giving voice, literally and metaphorically, to writers looking to get published, translated, or in simple need of camaraderie. Jack spoke more than 13 languages and translated the work of poets the world over, from the impoverished to the prized. Throughout his 87 years, he published a staggering body of work as a multilingual master, writing more than 100 volumes of poetry and prose, from his own work to the translations of other poets in Yiddish, French, Italian, Haitian, Russian, Albanian, and many more. Jack edited countless anthologies, journals, and collections, and even founded the Revolutionary Poets Brigade, a political movement of artists, poets, and thinkers using their work to create political resistance all over the world. He was a creative machine who existed to speak truth to power on the page and in his life.

Jack died unexpectedly in August 2021 from complications of COVID-19. If you know me, you know losing him, especially in this way, was a devastation I have not fully recovered from. In some ways, I’m still in denial, or rather, still reeling from it. Since his passing, I’ve written a lot about what he meant to me, how he shaped me as a young writer, feminist, and activist. (Just after his passing, I wrote this piece for the San Francisco Chronicle. I also wrote about Jack throughout Listening in the Dark—the book from which this page takes its name.)

I was a child actress who started at the age of 11, and though Hollywood was an industry I loved working in, it wasn’t one I loved working for. Jack nurtured the other creative side of me, a side that was very much alive and very much not acting. A side that wanted to confront parts of the industry I worked in—the misogyny and inequality. While the world mostly knew me as a TV star, Jack did not. To him, I was more than that: I was a whole universe that he knew I needed to explore. Jack taught me how to tap into a skill he had already honed so well: to harness anger over injustice and oppression and wield it like a powerful weapon on the page.

In my teens, he would send me books of writers he had translated or new books of his own work that had just been published. He would call our apartment and talk to my dad, then ask to speak to me. In his gruff voice he would say, “Kiddo. What are you writing these days? Send me everything.” And he meant it. Jack encouraged me to nurture and follow my observations: the healthy skepticism of my profession and what it expected from girls like me. He was probably the only adult in my young life, (except for maybe my English teacher, Laurel Schmidt), who didn’t think my acting chops were the best thing I had going for me. It’s not that Jack didn’t care about that part of my life, it’s just that, when it came to my writing, he cared more.

I have saved all the letters Jack ever wrote me. There are a lot. The early ones came with a lot of tough love: good, healthy feedback and editorial criticism for my writing that I needed to hear. It was not something I was used to. As an actress, I was mostly lauded by the adults around me who told me how great I was, how talented. My talents as an actress were celebrated, but with Jack, my talents as a writer were challenged, always with deep love and respect. Jack's encouragement and guidance of my young poetic voice is one of the biggest reasons I’m the writer that I am today.

Over time, my writing matured as I organically began to explore my own style, moving away from from the swooning odes to the writing style of my mentor. I would find myself heavily disagreeing with Jack’s editing of my work, pushing back on his critiques in ways I hadn’t before. Jack believed I needed to stop centering myself in my writing, that Hollywood was infecting my perception as a poet, my ability to write about topics outside of myself. “Your ego is already centered in your work as an actress,” he wrote to me once in a letter. “Don’t carry that into your work on the page. Think beyond yourself, to the many wars the world over worth writing about.”

But what I was beginning to understand that Jack could not was the difference between our lived experiences and how that might impact what we both write about. Jack was not a girl who grew up objectified for a living, expected to weigh a certain amount or look a certain way to be considered worthy. I could not just erase that part of my experience—that part of my career that demanded to be addressed in my writing. Why should I write about wars I have not lived through when I’m living through one of my own, right here, as a woman in Hollywood? After all, it was Jack who taught me how to fight on the page against oppressive systems just like the one I grew up in. I had to show him why centering myself in this way—my real, whole self—mattered.

Jack welcomed the pushback, and sometimes he disagreed. He knew better than anyone that my resistance to his criticism was a good sign that I was beginning to come into my own as a writer. Jack had no desire or time to placate a hobby of mine, and his letters to me reflected that. When I began to define myself as a writer on my own terms, separating my voice from his, he was proud, albeit a little dismayed, and our relationship evolved from mentor and student to peers.

As I got older, my feminism became more pronounced, and I used everything Jack taught me about transforming my anger into meaningful work. I began to branch out, applying my voice to different genres outside of poetry. Jack once told me, “You’re at your best when you’re writing from your rage,” and it’s true. I wrote a novel, non-fiction books, essays, and op-eds for the New York Times, The Cut and many other outlets. With each book and each new piece of writing, Jack was proud of me and of the writer and feminist I had become.

I was that little girl he would sit with in her parents’ living room, reading her revolutionary poets from El Salvador, Nicaragua, Italy, and China. I was that little girl who looked up to him so much, listening as he read new poems around the fireplace to our neighbors or to a crowd of thousands, out somewhere in the world. I was the girl who would put her pencil to paper not knowing what to write and finding a voice that was an ode to Jack's. A girl who wanted to be just like him when she grew up, and in some ways, she is.

In February of 2020, two weeks before the world shutdown, I was on a book tour for the paperback release of my book Era of Ignition: Coming of Age in a Time of Rage and Revolution. I visited San Francisco for an event in conversation with One Fair Wage’s Saru Jayaraman, a political organizer and activist. Jack was so taken by the conversation about systemic injustice in the workplace, from Hollywood to the restaurant workers industry, he went home and wrote a poem about it. It’s the first and only poem he ever dedicated to me, an arcane titled, “The Angranized Arcane.” (“Angranized” was a term I had coined to describe women who are angry and organized.)

Jack emailed me the arcane a week later and asked for my feedback. It was the first time he had ever done that with one of his poems. It was a beautiful, rich piece, an ode to feminist organizers and agitators the world over. I sent him my notes and he thanked me.

“Carabella Amber----,” he wrote back, “This is just what I wanted, grazie/ I'll probably be changing words throughout because my feeling is that the length of the Arcane is solid. You put your fingeron many points that’ll lead to changes----I'll send you the changes next week. Abbracciebaci---Jack”

As I write this, it dawns on me that that was the last time I ever saw him alive, in person. COVID-19 hit a few weeks later and a worldwide pandemic had begun. Like most people, we scattered to the wind, each of us dealing with the unpredictability, fear, and uncertainty of what might lie ahead. Jack hunkered down with his wife in San Francisco, and I did the same with my family in New York. I never did see the final edit of that poem.

In the end, I had the great joy and pleasure of returning the favor that Jack had given to me for so many years; to encourage his writing and support him in the editing of his work. In the end, the student became the mentor, if for just one brief moment.

I wonder if Jack ever finished “The Angranized Arcane.” If it’s floating around somewhere in his old apartment where his widow, the artist and poet Agneta Falk, still lives. Is it there somewhere, resting amongst all the writing and unpublished poems he left behind? This arcane, a living fact of us; a historical document in poetic form that tells our story—our forever unfinished work.

Who was your Jack Hirschman? Was there a teacher, a mentor, a friend that shaped or changed your life? I want to know all about them.

Path by Jack Hirschman

Go to your broken heart.

If you think you don’t have one, get one.

To get one, be sincere.

Learn sincerity of intent by letting

life enter because you’re helpless, really,

to do otherwise.

Even as you try escaping, let it take you

and tear you open

like a letter sent

like a sentence inside

you’ve waited for all your life

though you’ve committed nothing.

Let it send you up.

Let it break you, heart.

Broken-heartedness is the beginning

of all real reception.

The ear of humility hears beyond the gates.

See the gates opening.

Feel your hands going akimbo on your hips,

your mouth opening like a womb

giving birth to your voice for the first time.

Go singing whirling into the glory

of being ecstatically simple.

Write the poem.

Every bookshelf should have a book by Jack Hirschman. If you don’t own one, here are some I recommend. Order them from your favorite local bookstore or the links below. Let’s keep Jack’s work and legacy alive, together. For more titles and to learn more about Jack, click here.

Front Lines

All That’s Left

Only Dreaming Sky

Endless Threshold

Thanks for sharing your story. Beautiful and transient poetry.

This is touching and beautiful and sad to read, for all the reasons you’d expect, but also because I am so sorry for myself to have not had a mentor like yours, or any mentor for that matter. I feel like an orphan. I worry I’ll never grow into my full poet-ential.