A Look inside This Historic and Powerful Writers Strike

An interview with writer Eliza Clark on the WGA, unionizing, and the long road ahead.

This week, the Writers Guild of America (WGA)—a labor union comprised of thousands of writers in the entertainment business—went on strike in protest of large, inequitable problems facing the industry, including pay disparity for writers of streaming shows and films, the lack of clear and strong regulations around artificial intelligence and language-generating software like ChatBox, and so much more. According to the WGA’s official statement, “The decision [to strike] was made following six weeks of negotiations with Netflix, Amazon, Apple, Disney, Discovery-Warner, NBC Universal, Paramount and Sony under the umbrella of the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP).” Those negotiations proved futile, bordering on insulting, and so here we are, watching a historic strike that may not come to an end for a very long time.

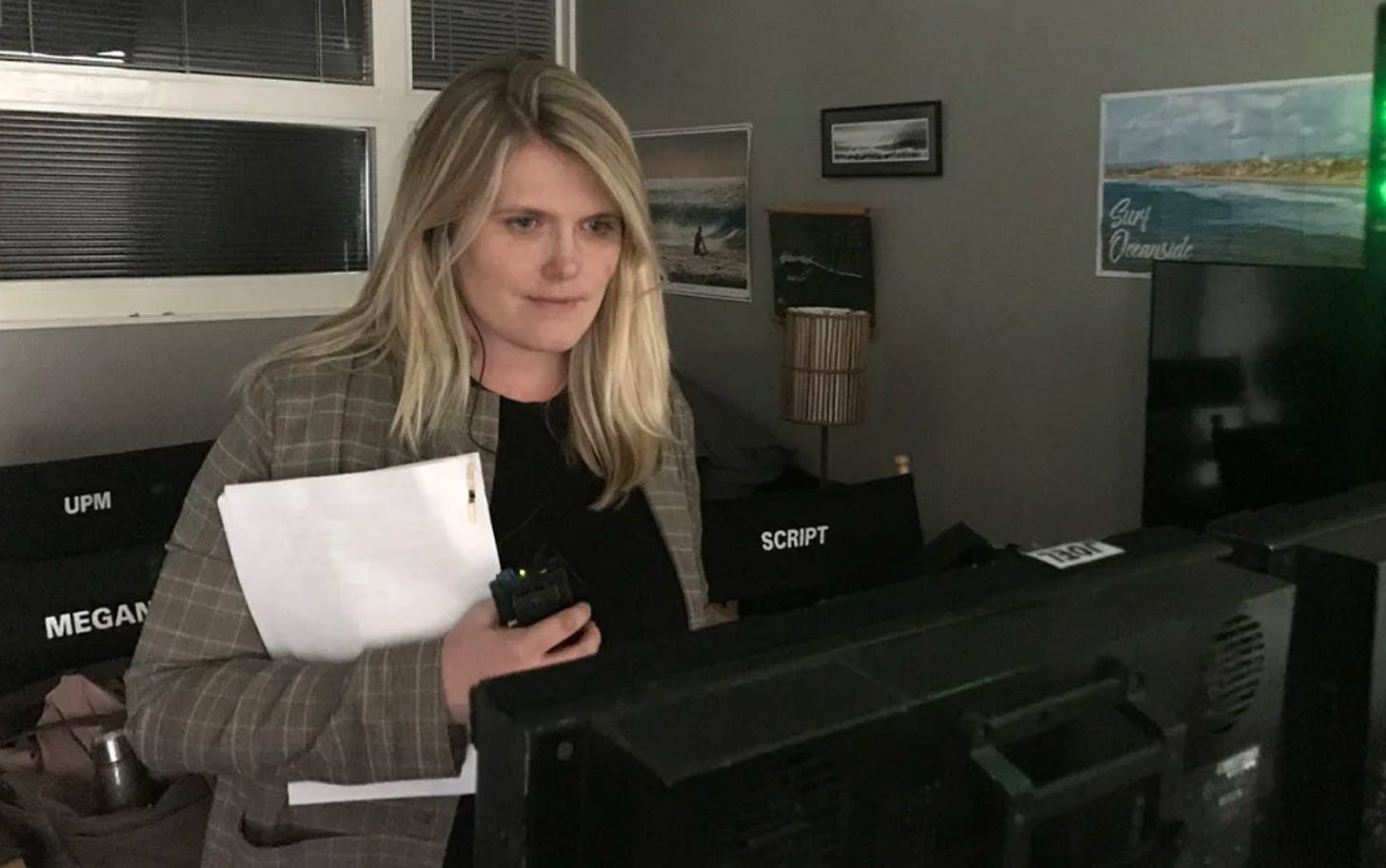

What used to be a job that could afford almost any television or film writer a decent living has now become a career that can barely cover a writer's rent. To give some important context to what’s taking place and why this strike is so important for the future of our favorite shows and films (and those that create them) I interviewed my friend, writer and producer Eliza Clark. You might remember Eli from one of our most popular posts here about my experience healing in the desert, but Eli is also a veteran of the entertainment industry, a prolific playwright, television writer, showrunner, and executive producer. She is the author of several excellent plays including Edgewise, which explores the intersections of capitalism, class, and sexism. In television, she’s created and worked on brilliant shows such as Rubicon, The Killing, Animal Kingdom, and Y: The Last Man, the last of which being where she and I met. Eli is one of the smartest and strongest writers I’ve ever had the privilege of working with, and so naturally she was the first person I thought of when the strike was approved. Below, we discuss the importance of this moment in history, how to stand behind unions when they strike, and what this all means for the future of the television and film we all love so much.

Amber Tamblyn: Eli, you are a beloved, veteran writer in our industry, having written some of the best television in the last decade, including Rubicon and Y: The Last Man. (I’m totally not biased, like, at all.) What is this writer's strike all about? Can you break it down for us?

Eliza Clark: Beloved! Thank you. You are beloved (by me and countless others, but I love you HARD, so maybe MOST BELOVED by me? If it’s a contest, I win). Okay, let’s talk about the strike. The last WGA strike was in 2007-2008 and lasted 100 days. The biggest issue on the line in that strike was whether or not the WGA would get any jurisdiction over the internet or what we now refer to as streaming. The WGA saw that these media conglomerates were seeking to change the nature of the business, and the union fought hard to ensure that writers could still make a living (and that writing for Netflix, for instance, would still be covered by the union rules of WGA). The strike in 2007 was prescient and important. It was a fight for the life of the business and for the careers of working writers. The WGA does not take striking lightly—there are thousands of people who rely on this business to feed their families, and we would not be striking if this were not a critical moment where the future of our work is on the line.

So here’s what this strike is about (bottom line): The cost of living in the two central hubs of the entertainment industry, Los Angeles and New York City, is sky high, and while there are a handful of writers who CAN afford to live in these cities, most cannot. Most writers are middle class, just trying to pay rent and make ends meet. If you look at our proposals and AMPTP’s counters, you’ll see that they are trying to grind us down to doing the same amount of work in a shorter amount of time and for less money. They want to turn us into gig workers and destroy our middle class. If they succeed, it’s the end of our health and pension plans. Those benefits won’t be sustainable if writers are only being paid per script and not at a weekly rate.

It used to be that studios would hire a writer to write a pilot episode, then they would shoot the episode and if the studio liked it, it would be greenlit to series. When the writers’ room was assembled after a show was greenlit, writers would be guaranteed a television season’s worth of work. Of course, when that season ended, there was no guarantee that you’d get another season or another job. Writers have always had to hustle for work and make paychecks stretch over long periods when no money was coming in. But now . . . it’s worse.

Over time, studios have started using “mini writers’ rooms.” These are just small writers’ rooms with fewer writers doing the same amount of work that a standard room would normally do. Except in some cases, mini rooms are actually doing more work because you’ve got less womanpower (or manpower, if you must call it that) breaking story in the room, writing outlines and episodes, creating presentations and pitches, etc. These mini rooms pay minimums in spite of the fact that the work is literally the same as any other writers’ room, lasts about ten weeks, and gives no guarantee that the show will ever see the light of day.

Writing for TV has a pay structure with minimums that were hard-fought by the Guild in past negotiations. You start as a staff writer on a TV show and progress through the levels, earning both experience and more money as your skills grow. The idea is that you are learning how to produce, becoming a producer, taking on more responsibility and preparing to one day become a showrunner/executive producer, etc. With the advent of mini rooms, companies have been forcing writers to repeat these levels ad nauseam without the kind of compensation they would receive in a regular writers’ room. Instead of writers getting to move up, both professionally and financially, they’re being forced to move in a circle without the standard assurances that someday they can make it to a place of comfort and sustainability in their career.

I have MANY friends who have been staff writers or story editors over and over again, with this cycle disproportionately affecting writers of color. For the last twenty years, staff writers have earned no additional money when they write a script, even though everyone else on staff gets paid for their work in the room and additionally for their script. The AMPTP has decided to budge on this point just in time to stop paying us weekly and turn us into gig workers. Just in time for it not to matter.

All this to say, simply: it’s become nearly impossible to move up the ladder. Mini rooms also mean that writers are working on shows and leaving them long before the show is ever in production, which means they aren’t getting valuable on-set experience. Amber, you can attest to this as an actor and director: having a writer on set is invaluable. There is a lot of writing that happens on set—actors have questions, directors need something changed for blocking, etc. The week before an episode is shot is called prep, and an enormous amount of writing happens during this week where scenes are dropped or changed to shift the budget or our collaborators have questions and notes. Writers being on set isn’t “nice to have,” it’s a must have. Good TV and film begins with a script—and the writing isn’t done until the final mix. The reason why there are shows as good as Succession and Barry and Search Party and The White Lotus and Reservation Dogs and Yellowjackets or movies you love like Everything Everywhere All at Once is because of brilliant writers.

You’ll see a lot of WGA writers on Twitter and in the picket lines saying, “Rejected our proposal. Refused to make a counter.” That’s because that was how the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) responded to a lot of extremely reasonable proposals. We asked them to “guarantee a second step if hired for a screenplay for less than 250% of minimum” (meaning, “stop forcing screenwriters to do multiple drafts before they ever see a dime”) and the AMPTP said instead they’ll hold a meeting about “screenwriters’ free work concerns.” I mean . . . are you fucking kidding me? To quote Succession’s Logan Roy, “You are not serious people.” We also proposed regulations on the use of artificial intelligence: “AI can’t write or rewrite literary material; can’t be used as source material; and MBA-covered material can’t be used to train AI.” To this, they said no, and instead offered to have a meeting about AI like some consolation prize. Believe me, none of us want scripts written by robots and algorithms. If you ever want to see something original and groundbreaking again (or honestly, if you ever want to see anything that isn’t a mashup of shit that you’ve already seen), we can’t let these companies start using ChatGPT to create art. It is a dangerous, slippery slope. I can’t believe that’s even something that needs to be said. This is an existential threat not only to our business, but to who we are as human beings.

These corporations leapt into streaming headfirst without understanding any of the consequences or how drastically it would affect the livelihoods of people who are the only reason anything can be streamed in the first place. We asked for less than 3% of billions of dollars of profit built on our work—work that we generate from scratch, entirely from our BRAINS—and they wouldn't do it. The CEOs of these streaming companies are laying off workers, gutting our industry, and then buying a second yacht because the first one doesn’t have a helipad.

Before streaming, there was a business model in place in film and TV that made sense and made everyone money—ad sales that rewarded high viewership. Seasons of TV were usually twenty-two episodes long, which essentially made writing for TV a year-long gig, and in between jobs, residuals (essentially a royalty for the re-airing of creative work) kept people alive. Streaming has done away with the ad model almost entirely. Now, writers have absolutely no idea how many people watch their show. (Those numbers are closely guarded secrets, and being transparent about how many eyeballs we have watching our shows was one of the things the AMPTP would not even consider.)

Amber: Why is this strike important, right now, at this moment in time? If someone were to ask you, "Why not do this later, next year, or another time?" what would your answer to them be?

Eliza: This is a pivotal moment in our business. These companies, under the umbrella of the AMPTP, have been cannibalizing each other for years now. What used to be a healthy competition between many studios has become a handful of mega corporations controlled predominantly by tech billionaires. Writers are hurting. Most actors are hurting. For many, it’s impossible to make a decent living. Forget buying a house, there are people who can’t make their rent, people who are taking on second jobs. The corporations want to turn our business into a gig economy. That’s not good creatively. It’s not good for audiences, and it’s not good for any of the workers in Hollywood. There are many executives at these companies who I love, who are decent, kind, thoughtful, and creative people. Many of them are being laid off by the thousands so that corporate billionaires can buy private jets. I wish it weren’t that simple and sad, but it is. Hollywood CEOs making 250 million dollars a year are saying that 9,000 writers should split an 86 million dollar increase over three years? MAKE IT MAKE SENSE.

These companies are crying “poor,” but they bear much of the responsibility for why Hollywood is so broken right now. Instead of focusing on quality programming worthy of investment, these companies are entirely focused on new subscribers and new subscribers alone. They’re operating like a pyramid scheme, and that can’t last. Your favorite shows are getting canceled, not because they aren’t good or because they don’t have an audience . . . They’re being canceled because unless they bring in millions of new subscriptions to the streaming service quickly, they are viewed as failures.

You pay hundreds of dollars in subscription fees to streaming services who don’t care about you because you’ve already subscribed. And if they don’t care about their audiences, why should they care about those of us who write for those audiences?

Amber: What do you think is most misunderstood about a strike of this magnitude and the writers and organizers behind it?

Eliza: The AMPTP will be putting out stories about the most successful writers in our business to make it seem like we don’t have it that bad, like this one about the historic deal writer Phoebe Waller-Bridge recently struck with Amazon.They want the world to think of us as rich people who have dream jobs who just need to manage our expectations and be grateful for what we have. That’s a lie. Yes, there are WGA members who have made a lot of money. But the ugly truth is that while Phoebe Waller-Bridge is making good money, she is still being compensated at a fraction of the BILLIONS of dollars she is bringing in for these same companies. Fleabag was a masterpiece, and Amazon reaped the benefits. If they make billions of dollars off her creative labor, she ought to be paid a percentage of that.

But let’s put that aside because this is not the norm. Most writers are solidly middle class. The nature of our business is that we have no idea where the next paycheck is coming from and when. We have to make that money last for months between projects. And we have to pay agents, managers, and lawyers who help us make our deals. Because the business is now swimming in mini rooms, we may work for ten weeks out of an entire year, and that’s it. To add insult to injury, these companies notoriously pay writers as late as they possibly can, so writers end up doing a ton of unpaid labor in development and then waiting months before ever seeing a paycheck.

Amber: How do unions like the Writers Guild of America help their members get what they need? What's so valuable about organized labor and collective bargaining?

Eliza: Unions are the reason we have weekends, paid sick days, bathroom breaks, workplace safety, and a million other necessary rights. We’ve all watched Newsies, right? We all need unions. UNIONS FOR EVERYONE! In terms of the WGA’s current labor struggle: these companies are banking on the fact that most of us love what we do, and in spite of the ways they exploit us, they know that we care about the work. They are using the fact that we are artists against us. They think that we will do a good job even if they disrespect us and treat us like cogs in a machine, and listen, that’s a good bet. We love what we do. And most of us want to do a great job. And that’s why we are so lucky that we have a strong union that will say NO and push back when we’re being taken advantage of.

When we band together collectively, we wield a lot of power. There are a lot of changes that need to be made in Hollywood. Writers are being exploited, but so are actors, directors, and most especially, our crews. In past labor struggles, the AMPTP has tried to divide the Hollywood unions, pitting us against each other. You’ll see articles in some of the trades saying that below-the-line workers (crew members) are being thrown under the bus by the strike. Let’s be clear: what we have asked for is absolutely reasonable, and the companies didn’t even seriously come to the table. The AMPTP is responsible for this strike, and the unprecedented solidarity among the unions is because we all know that what we are asking for is reasonable. We make the work that makes them billions. We do not want to be ground down into gig workers. The AMPTP cannot divide us this time. Workers all over this country are waking up to the fact that corporations only care about profits. They want to pay all workers the least amount of money they can for the most amount of work so they can make record profits while the rest of us suffer.

The WGA is a strong union with brilliant people on the negotiating committee and the board. They have volunteered their time to try to win us a fair deal. They deserve our gratitude and solidarity. And these companies deserve our righteous anger. When workers stick together, we win. And we will win.

Amber: Final question: how can people who are not in the guild support the WGA and this strike? What are the best ways people can show up to fight in this moment?

Eliza: You can picket with us! COME PICKET WITH US!!! You can find out where people are picketing in Los Angeles and New York here. And also: do not be a scab. The way to make this strike both effective and not drag on forever is to really be united, pencils down. If you have a desire to ever be in the WGA, any work that you do for these companies during a strike will be considered scabbing, and you will never be allowed to join. Of course you should write, write as much as you want, but until the strike is over, your writing should not be submitted to these companies, and you should not be taking meetings with these companies. It is in everyone’s best interest to show these corporations how important writers are. If you’re a writer, even if you are not yet in the WGA, we are striking for you too. We are striking for the future of writing. Stand with us.

If you have any more questions, check out the strike rules here.

You can also donate to the Entertainment Community Fund here, to support our colleagues who may be impacted by this strike. Choose “film and television” in the drop down menu.

The impact of a strike depends on solidarity and unity. We all need to be in this together. Pencils down, laptops closed. #WGASTRONG

Let’s fucking go.

Thank you for this insight into an issue about which we in the public know far too little (okay, most of us know far too little about most things, but that's a whole other issue). I have a couple of friends "in the industry" and I know how hard they work, and for what is often not much money (and as Ms. Clark noted, the flow of that money is unreliable and unpredictable). Good luck to the strikers!

Thanks for this, both! Very helpful summary. I can't think of a better way to celebrate May Day! Dusting off my Little Red Songbook contrafacta and joining in (or maybe I'll actually finish my article on the LRSB...)